Before 1933, Rudolf Kayser was the chief editor of the Neue Rundschau, the most influential literary journal published by the S. Fischer publishing house. Kayser was in contact with many German speaking authors, among them also Stefan Zweig. In this letter, written in London, Zweig refers to his plans to stop his cooperation with Fischer, which, following the Nazi takeover, was about to cancel all contracts with Jewish authors. He also mentions the fact that he is compelled to leave his home and his collections, and that he has to start a new life, tired as he is. Zweig mentions the great success of the biography of Marie Antoinette and his study on Erasmus of Rotterdam, whose fate Zweig regarded as similar to his own: a weak intellectual in harsh times.

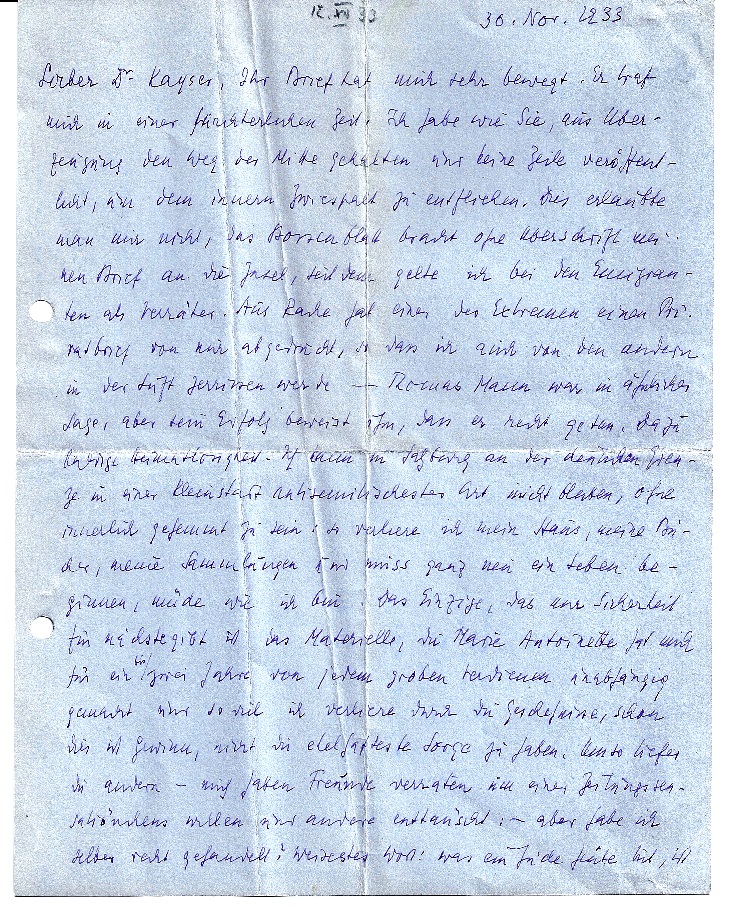

30.11.1933

Dear Dr. Kayser,

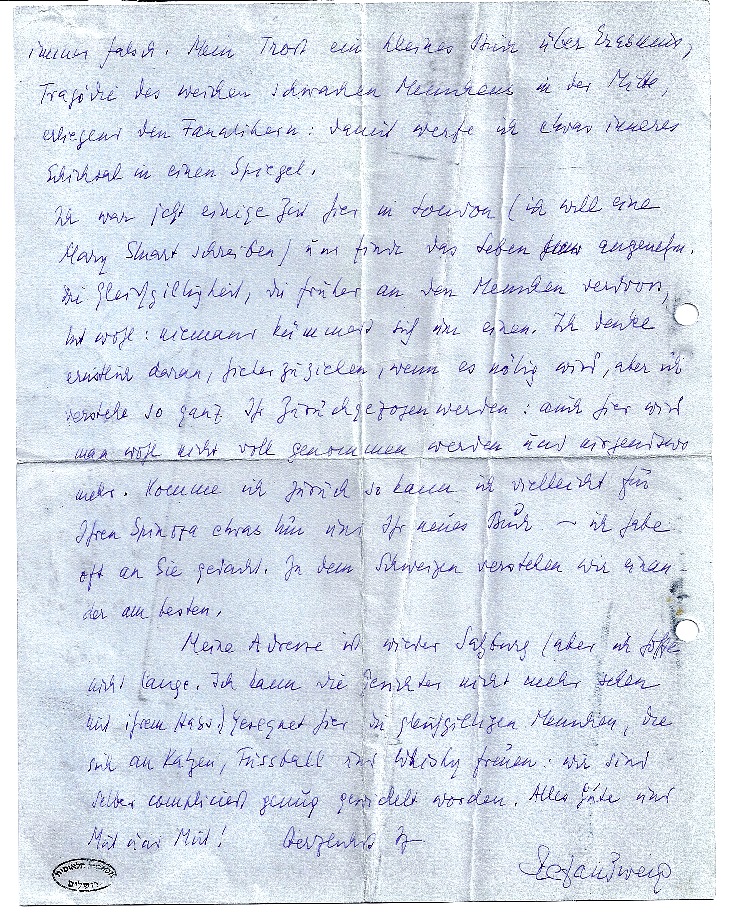

Your letter moved me deeply. It reached me at a terrible time. I have, like you, been holding onto the 'middle way', and have not published a single line in order to escape my inner conflict.. (However) I wasn't allowed to do so, as the Börsenblatt published my letter to the Insel without a headline, and since then I am considered a traitor among the emigrés. Out of revenge one of the extremists published a private letter written by me, and now there's gossip in the air about me – Thomas Mann was in a similar situation but his success proved that he was right. Soon [I will be] without a homeland. I cannot stay in Salzburg, a small town of the most anti-Semitic type, close to the German border, without being strongly inhibited: and so, I am losing my home, my books, my collections and have to start a completely new life, tired as I am. The only [positive] thing is that my economic situation is secure for the near future. Marie Antoinette provided me independence from the need to earn money for one or two years, and given all that I am losing because of the circumstances, it is beneficial not to have abhorrent economic worries. Much worse the [situation of the] others – I was betrayed by friends for a small sensation in the newspapers, and others disappointed me – did I handle this correctly? The wisest saying is: what a Jew does today is always wrong. My consolation is a small book on Erasmus, the tragedy of a fragile weak man who is [stuck] in the middle and defeated by the fanatics: by doing so, I throw inner destiny in some way into the mirror.

I have been here in London for some time (I am going to write a Mary Stuart) and I find life pleasant. The indifference of people, which once used to bother me, now pleases me: people are not concerned with one another. I am seriously considering to move here if it becomes necessary, but I understand completely your withdrawal: here too one is not taken seriously and probably nowhere else. If I return perhaps I could do something for your Spinoza and for your new book – I have been thinking about you often. Through silence we understand each other best.

My address is again Salzburg (but I hope not for long. I cannot bear their faces full of hate any longer). Blessed be the indifferent people here who enjoy cats, soccer and whiskey: we are complicated enough ourselves. All the best and courage and courage!

Most heartedly yours

Stefan Zweig